San Andrés rises gently from the Caribbean, part of Colombia but closer to Nicaragua, the largest island in an archipelago claimed by the Spanish, colonized by the Puritans, worked by slaves, and home to Arab traders, migrants from the mainland, and the descendents of everyone who came before.

For Victoria – whose origins on the island go back generations, but whose identity is contested by her accent, her skin color, her years far away – the sun-burned tourists and sewage blooms, sudden storms, and ‘thinking rundowns’ where liberation is plotted and dinner served from a giant communal pot, bring her into vivid, intimate contact with the island she thought she knew, her own history, and the possibility for a real future for herself and San Andrés.

This is the second-to-last novel of an old Charco Press bundle I bought. Charco Press is a small but mighty independent publisher which started in 2017 in Scotland and specialises in translation of novels from Latin America. Their books are out of the ordinary, make me discover new horizons, and they also look really pretty on my bookshelves. Oh, and they do bundles, which is why I’ll read their books without checking anything about them. It’s led to amazing discoveries and bitter disappointments.

Salt Crystals is somewhere in between, which was statistically predictable. It’s definitely on the good side, though.

San Andrés not being Colombian is a whole thing.

But first thing first – I got this book, wrote down the country (Colombia), thought « yay, another box checked for the Around the World reading challenge » and put it down to revisit it about a year and a half later. Which brings us to now. I started reading, and immediately I opened Wikipedia, as one does, to check where in Colombia San Andrés was.

The answer seems to be: not.

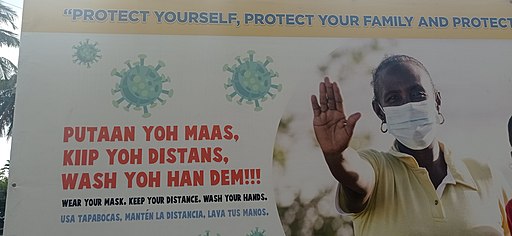

In San Andrés, people speak Creole English. People get many tourists and they don’t vibe with them too much, but they still like those better than the Colombian government, which is very far away and doesn’t seem to care about much outside of collecting taxes. The culture is not Colombian, the language isn’t theirs, and the people… well, the people make a big deal of being Raizal, or native, which according to Wikipedia is an ethnic group not defined by race which is sometimes black and usually speaks English Creole but not always and also is separatist?

I’m glad Wikipedia seems as confused as I am, because that’s pretty much where the book got me.

Anyway. Our protagonist, Victoria, is a woman who lost her parents in a car accident, left her cheating husband, lives and eats according to her glucose monitor because she’s diabetic and will faint if her blood sugar is too high or too low, and decides to go « back home » to San Andrés, a place she hasn’t visited since she was a kid.

When she gets there, she faces an identity crisis. See, Victoria is Raizal, a native islander. Except she hasn’t been here in fifteen years, she never learned Creole because her grandmother was very insistent on her speaking British English, her Spanish has a strong mainland accent, and she passes as white when Raizal are most often black. But Victoria keeps going and, from one blood test to the next, she rediscovers her island and does research on her ancestors, finally figuring out how one can be Raizal and white.

I really liked this book! Sometimes, it wasn’t the easiest to read, as the original is in three languages (Spanish, English and Creole) and the translated version keeps the Creole as is, and I love when translators do this. Our main character has to focus and work hard to understand her friends, and so do we when we read these lines of dialogue. She feels like a fish out of the water, and so do we. It’s perfect.

I found Victoria’s diabetes really well-incorporated as a key element of the whole plot. It’s not just that she has diabetes − the illness brings her more than once to look for emergency food and meet new people or find new information based on this, and we see breadfruit and sugar cakes bringing her closer to her heritage in a way that I enjoyed. Climate change and the terrible balance that can’t be achieved between tourism, growth, and the environment, broke my heart a couple of times and are very well written, with clear explanations that don’t feel like lectures. And as I already said, the core of this novel is identity and how one justifies belonging to a nebulous identity that they officially hold (through the citizenship card Victoria has), how one reminds people they’re « from here », they’re « one of us » when nothing points towards it.

The ending, set during the devastating Hurricane Otto, brings the novel to an abrupt end and leaves me asking a hundred different questions. If you read the novel, reach out, we need to talk!

I love Charco Press and really liked this novel, so I wrote a review for it.

The final month of 2023 is finally starting and the year has been long and transformative. I’ll have a lot to say in my recap…